For the 150 families who have their cornfields and citrus groves surrounding the Maya Train maintenance base in Felipe Carrillo Puerto, Quintana Roo, accessing their plots and harvesting their crops has become nearly impossible.

The facilities at this maintenance base—there are two others on the Yucatán Peninsula: in Xpujil and Puerto Morelos—include a workshop, an administrative building, a National Guard detachment, and a large, completely empty parking lot.

They were built by the National Fund for Tourism Development (Fonatur) on an embankment of about 14 hectares, which is the only access road to the surrounding plots, leaving them sunken a couple of meters. Furthermore, Fonatur installed a fence between the crops and the embankment, which must be climbed over to reach the cornfields.

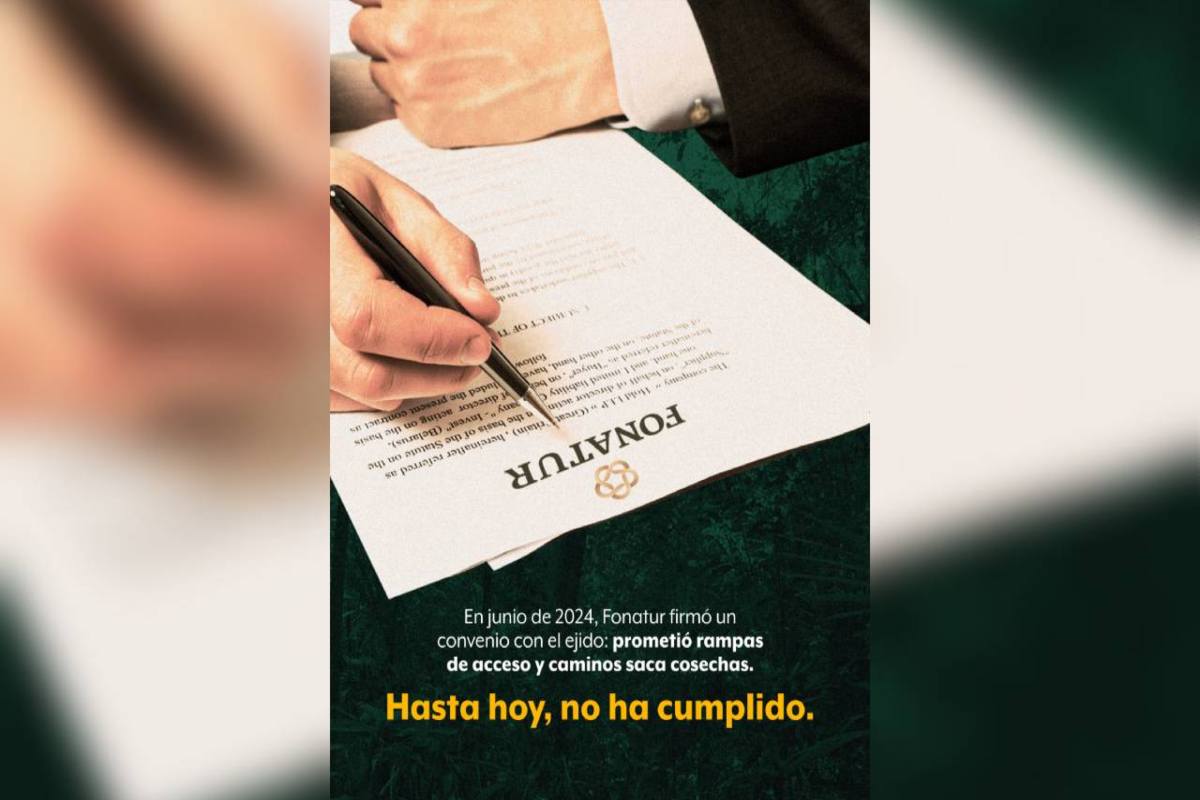

“On June 18, 2024, to resolve the problem, Fonatur signed an agreement during an ejido assembly. They promised to build access ramps to our plots and farm-to-market roads,” says Carlos Koyoc Pacab, president of the Oversight Council of the Felipe Carrillo Puerto ejido. “However, to date, they haven’t built anything.”

Between November 15 and December 15, 2019, 15 regional informational and consultative assemblies were held in the five states slated for the construction of the Maya Train. Some 300 residents of the municipality of Felipe Carrillo Puerto met in the community of X-Hazil Sur, representing 71 communities.

“At the assembly, they said the Maya Train was going to bring many benefits, but that wasn’t the case,” states Elías Be Cituk, who was then the ejido commissioner of Felipe Carrillo Puerto. He lamented that the megaproject attracted many military personnel but no tourists, and furthermore, it generated problems that the authorities failed to mention during the assembly.

In fact, according to the Office in Mexico of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), during the information phase of the Indigenous consultation process, the authorities referred only to the potential benefits of the project and not to the negative impacts.

“During the observed sessions, participants repeatedly asked about the impacts without receiving a clear and complete answer,” the UN stated. “The absence of impact studies or the lack of dissemination of such studies makes it difficult for people to define their position on the project in a fully informed manner.”

Elias Be Cituk also states that on December 15, 2019, during the assembly in X-Hazil Sur, the authorities never presented a copy of the environmental impact studies for the Maya Train, nor for the dozens of quarries that the Ministry of National Defense (Sedena) built in Felipe Carrillo Puerto.

“The [impact] studies haven’t been done, that’s why this is just a general consultation about whether or not the train should go ahead. Specific consultations will be held later in the communities about whether there will be any impact on the environment and culture,” stated Hugo Aguilar Ortiz in December 2019, then coordinator of the Indigenous Rights Program of the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples (INPI) and current Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation (SCJN).

However, once the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for section 6 of the Maya Train was published, no specific consultation was held in Felipe Carrillo Puerto. In the months and years following the December 2019 assembly, the government’s outreach to the communities focused primarily on reaching agreements based on emerging needs. Among these was the agreement that Fonatur signed with the ejido of Felipe Carrillo Puerto on June 18, 2024, following the problems that arose from the construction of the Maya Train maintenance base.

Broken Promises

From the overpass that crosses the Maya Train tracks, the railway maintenance depot looks like a gray stain on a vast green canvas of cornfields and citrus groves.

Just below the overpass, where the dirt road leading to the plots begins and runs alongside the maintenance depot, there are barbed wire fences. Carlos Koyoc Pacab says Fonatur put them up to partially block access.

“We’re worried they’ll completely close access to this road, which leads to our land. The train didn’t bring us development; it was a disappointment,” says the farmer. “The government didn’t keep its promises: not only did they not build the access ramps to the plots, but they also failed to build the bridge to transport our crops and the irrigation wells we had agreed upon. And they still need to pay for the damage they caused during construction, when they destroyed our citrus trees.”

Source; animalpolitico