Dengue continues to invade Mexico. The disease, which has accumulated more than 110,000 cases and 262 deaths this year, has broken out in states in the north of the country where it was barely present before, such as Jalisco and Nuevo León. At the moment, only Mexico City and Tlaxcala remain immune to the bite of the aedes aegypti, a mosquito that adapts more and more quickly to new territories. Mexico’s urgency to control this disease is part of the worst dengue crisis in the history of the American continent.

The figures have been warning for some time. If in 2022 the count of confirmed cases in Mexico closed at less than 13,000, it reached 56,000 in 2023, and already more than 110,000 infected in 2024 (almost half of them with severe dengue), according to the Ministry of Health. “We are facing an exponential increase,” says Veracruz researcher Luis del Carpio, “dengue used to be associated with the rainy season, but now we have had dengue all year round, we are approaching winter and the cases continue.” In the latest report published by the General Directorate of Epidemiology, which updates the data weekly, as of November 20, 262 people had died from the virus, while last year on this same date 132 were recorded. In addition to the increase, the change in distribution is surprising.

Jalisco is this year the entity with the most confirmed cases of dengue. The State has reached 17,100 infected and 26 dead; on the same date last year, it only recorded 740 patients and two deaths. The example is repeated in other entities in northern Mexico where dengue had barely been present. In Nuevo León, 71 cases were confirmed until November 2023 and there are already more than 9,200 in 2024; they have gone from zero deaths to 12. It also happens in Coahuila, which goes from 127 infected to 4,285 in one year, or in Sinaloa, which goes from 163 to 3,961.

Behind these outbreaks is a mosquito that takes advantage of global warming, soil changes and rainfall patterns to survive and thrive in places that were previously unfavorable to it. “Climate changes are causing the dengue vector to have more dominance. Before, the infected regions did not normally exceed 2,000 meters, now it has overcome that brake. Mosquitoes are conquering these new territories and if there are mosquitoes there is a risk of the virus,” explains Del Carpio, a clinical virologist. In addition to these new regions, dengue continues to wreak havoc in Veracruz (7,000 cases), Guerrero (6,400) and Morelos (6,300), and the highest incidence rate is recorded in Colima with 4,800 cases (it had only 400 last year).

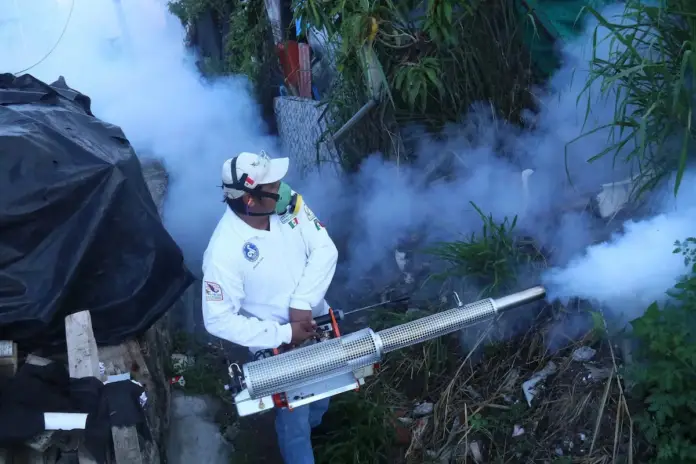

In addition to the numbers, Del Carpio, who is part of the Mexican Society of Virology, explains that a change in variant has been identified. While until 2022 DEN-2 predominated, associated with milder symptoms such as fever, vomiting or muscle pain, for two years now DEN-3 has dominated, which is much more aggressive and can lead to more atypical and dangerous conditions such as encephalitis or hepatitis. The virologist urges the authorities to address the crisis. “This situation is due to a set of climatic factors, mutations specific to mosquitoes, but also because governments have stopped doing their vector control, such as fumigation. It is also important to scrap and provide information to the population,” says the doctor.

The alarm is not exclusive to Mexico. Dengue is bleeding America. The continent had never recorded figures as high as those of 2023, with 4.1 million infections and 2,049 deaths, according to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Countries like Argentina have faced the deadliest crisis in their history, and there are record cases in Bolivia or Brazil. Behind this health emergency is the aedes aegypti, a mosquito extremely skilled at adapting to humans. This insect lives in stagnant water, preferably clean, and usually forms breeding grounds in wells, flower pots or containers in which water remains after irrigation or rain.

The mosquito, which has recognizable black and white legs, is cruel to the elderly and especially to children; almost 50% of those sick from its bites are under 18 years old. According to data from the Ministry of Health, this year in Mexico, dengue has primarily affected children between 10 and 14 years of age, with more than 16,000 cases recorded, both in the mildest form and in the form with more warning signs.

The Aedes mosquito transmits the so-called arboviruses, dengue, Zika and chikungunya. Some countries, such as Brazil, have opted to test a vaccine in public health. Others, such as Honduras or Colombia, have opted to avoid being bitten by the disease, for example with the so-called Wolbachia method, which consists of releasing modified Aedes mosquitoes with the Wolbachia bacteria, incapable of transmitting dengue, so that they reproduce with the local population and end up replacing it. This practice, which was already tested in Mexico in Baja California (still without results to analyse), managed to declare Australia free of dengue or reduce the incidence by 77% in Indonesia.

Source: elpais