In the shadow of a massive crucifix, the construction workers of the Mexican border town of Ciudad Juarez are building a small city. A tent city.

In the former fairgrounds, beneath an altar built for a Mass by Pope Francis in 2016, the Mexican government is preparing for the thousands of deportees it expects to arrive from the United States in the coming weeks.

Ciudad Juarez is one of eight border towns along the 3,000-kilometer border where the country is preparing for the expected wave of expulsions.

Men in boots and baseball caps climb atop a vast metal structure to cover it with a thick white tarp, erecting a rudimentary shelter to temporarily house men and women who look exactly like them.

Temporary workers, domestic workers, kitchen staff and farmhands are likely to soon be among those sent south as what President Donald Trump calls “the largest deportation in U.S. history” gets underway.

In addition to protection from the outdoors, deportees will receive food, medical care and help obtaining Mexican identity documents under a program to support deportees that President Claudia Sheinbaum’s administration calls “Mexico Embraces You.”

“Mexico will do everything necessary to care for its compatriots and will allocate what is necessary to receive those who are repatriated,” Mexican Interior Secretary Rosa Icela Rodriguez said on the day of Trump’s inauguration.

For her part, President Sheinbaum has stressed that her government will first address the humanitarian needs of those who return, saying they will be able to benefit from her government’s social programs and pensions, and will be able to work immediately.

She urged Mexicans to “stay calm and cool-headed” about relations with President Trump and his administration, from deportations to the threat of tariffs.

“With Mexico, I think we’re doing very well,” President Trump said in a video address to the World Economic Forum in Davos last week.

President Sheinbaum has said the key is dialogue and keeping channels of communication open.

However, she acknowledges the potential strain that President Trump’s declaration of an emergency at the U.S. border could put on Mexico.

An estimated 5 million undocumented Mexicans are currently living in the U.S. and the prospect of a mass return could quickly saturate and overwhelm border cities like Juarez and Tijuana.

A difficult task

This is a matter of concern for José María García Lara, director of the Juventud 2000 immigrant shelter in Tijuana. As he shows me around the facilities, which are already almost at capacity, he says there are very few places where he can accommodate more families.

“If we need to, we can perhaps put some people in the kitchen or the library,” he explains.

But he admits that there will come a time when there will be no more space, and donations of food, medical supplies, blankets and hygiene products are not enough.

“We are being hit on two fronts. First, the arrival of Mexicans and other migrants fleeing violence,” says García.

“But we will also have mass deportations. We don’t know how many people will cross the border needing our help. Together, these two things could create a big problem,” he warns.

In addition, another key part of Trump’s executive orders includes a policy called “Remain in Mexico,” under which migrants awaiting dates to make their asylum cases in a U.S. immigration court would be required to remain in Mexico before those appointments.

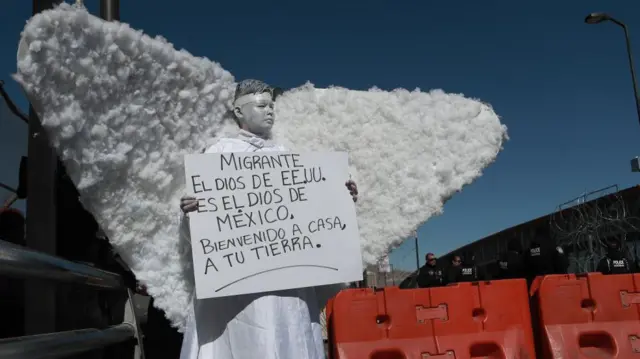

CaptionMexico has also tightened security on its side of the border to try to stem illegal crossings.

When “Remain in Mexico” was previously in effect, during Trump’s first term and under President Andrés Manuel López Obrador in Mexico, Mexican border cities struggled to cope.

Human rights groups have also repeatedly denounced the risks migrants were exposed to by being forced to wait in dangerous cities where crime related to drug cartels is rife.

This time, Sheinbaum has made it clear that Mexico does not agree with the plan and will not accept any non-Mexican asylum seekers from the U.S. while they await their hearings.

It’s clear that “Remain in Mexico” only works if Mexico is willing to comply. So far, it has drawn a line.

President Trump has deployed some 2,500 troops to the U.S. southern border, who will be tasked with carrying out some of the logistics of his offensive.

In Tijuana, meanwhile, Mexican soldiers are helping prepare for the aftermath.

Authorities have set up an event center called Flamingos with 1,800 beds for the returnees, with troops bringing in supplies, setting up a kitchen and showers.

As President Trump signed executive orders last Monday, a minibus rolled through the gates at the Chaparral border crossing between San Diego and Tijuana, carrying a handful of sports.

A few journalists had gathered to try to speak with the first sports of the Trump era.

But this was a routine deportation, likely weeks in the making and nothing like the papers Trump was signing before an excited crowd in Washington, D.C.

Symbolically, though, as the minibus sped past media waiting outside a government-run shelter, these will be the first of many.

Mexico will have to work hard to take them in, house them and find them a place in a nation some will not have seen since they left as children.

Source: bbc