On November 30, 2000, the night before President Vicente Fox Quezada’s inauguration, at midnight, residents near the Frissell Museum in the magical town of Mitla heard loud noises coming from inside. Many people gathered and, to their astonishment, saw men smashing all the museum’s display cases and removing the artifacts, loading them onto a flatbed truck. Broken glass and empty niches were left behind. In what amounted to an hour-long heist, the crowd of onlookers asked what was happening, and the men removing the beautiful pieces from the museum replied that they belonged to the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH).

The people of Mitla, accustomed to INAH disregarding municipal authorities, watched the spectacle unfold, their only protests being shouts of “Don’t take our pieces!” No authority intervened. And the truck took everything its occupants loaded with extreme violence. They left the display cases, which American Express had paid for, destroyed, depriving the residents of Mitla and visitors of their enjoyment.

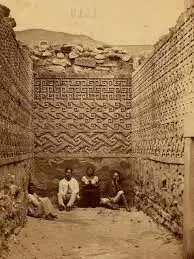

The large wooden door through which the assailants entered was closed again. In other words, no one forced the large access door, which had wooden beams that acted as locks. From this distance, it’s understood that someone opened it from the inside, or the assailants themselves jumped over a fence and opened the door. This museum was under the administration of the University of the Americas (UDLA), presumably the UDLA in Mexico City, since the recipient of the entire house that housed the museum, a large library of books specializing in archaeology, a hotel, and a restaurant, was the former “Mexico City College” on September 17, 1959, before a notary public, with two inventories registered with the INAH (National Institute of Anthropology and History). The house contained the Frissell Collection and the Howard Leigh Collection.

Now, the deafening silence of the INAH (National Institute of Anthropology and History) and the UDLA (University of the Americas), who failed to file any complaint or offer any explanation to the municipal authorities, compelled the City Council at that time to commission the Municipal Attorney, Rufino Aguilar Quero, who had worked at the museum since his youth, to travel to Mexico City to the University of the Americas (UDLA). He carried official letters from the Mayor, but upon arriving at the University, he discovered that the Vice-Rector was in charge of the Rector’s office. Upon learning of the Municipal Attorney’s presence, the Vice-Rector contacted the newly appointed Secretary of Public Security at the national level, Alejandro Gertz Manero, who, although no longer Rector of the University, remained involved in the administration of the institution. This was explained by the aforementioned Trustee, who returned with an absolute rejection in response to the municipality’s demand for an explanation of what happened on the night of November 30, 2000. The same was true for the INAH, which at that time was directed by the ethnologist Sergio Raúl Arroyo, who instructed the Director of the INAH-Oaxaca Center to send an official letter to the aforementioned Trustee to address his concerns. And by official letter number SJ-403-77/050, dated February 19, 2001 (one month and 19 days after the attack on the museum in Mitla), addressed to the mayor of San Pablo Villa de Mitla, Luis Monterrubio Méndez, with a copy to Governor Murat, and also to the Director of the Public Registry of Monuments and Archaeological Zones, he offered to conduct an on-site inspection of the Frissel Collection in the presence of the Head of Security of that Institute. In the same letter, he arrogantly asked the Mayor that, if he was truly committed to protecting this heritage, he should comply with the law regarding the security of the Collection.

In reality, it’s unclear why this on-site inspection never took place, primarily due to a lack of trust in condoning a midnight robbery that went unreported, was completely out of the ordinary, and had no explanation. Furthermore, the municipal authorities lacked an expert to identify the contents of an inventory of 40,000 pieces from the Frissel collection and 600 highly selected pieces curated as Zapotec pre-Hispanic art, all without expert oversight. They were aware that, commissioned by the university, 600 replicas had been made for a supposed university museum.

Source: imparcialoaxaca