In the heart of Durango’s historic center, where modernity barely touches the ancient walls, stands a stone structure that holds more than architectural history: it preserves the whispers, absences, and scars of those who lost the will to live and chose it as the point from which to end their days.

This is the Analco Bridge, a place that, beyond connecting two points in the city, connects the memory of those who took their own lives there with the consciences of those who still walk along its banks, although for a time they avoided using it.

Its steps seem to bear witness to the tragedies that occurred there. Climbing this bridge is like feeling all those emotions, for on its steps one can read encouraging messages such as: “Don’t do it, there are reasons to live.”

For years, the Analco Bridge has been a silent witness to Durango’s evolution. Its origins date back to the 18th century, when it was built to connect the Analco neighborhood with the rest of the city.

In Nahuatl, Analco means “on the other side of the river,” and since its founding, this neighborhood has been an enclave of popular identity, with Indigenous and working-class roots.

The bridge, made of quarry stone and lime, served as a pedestrian crossing over the El Tunal stream—now channeled—and was part of the urban fabric of a city that grew to the rhythm of commerce, mining, and religious devotion.

But over time, the bridge ceased to be just an infrastructure project. It unwittingly became an emotional turning point. A place where, according to testimonies, many people chose to take their final step.

For years, neighbors and passersby avoided it, not out of physical fear, but because of the emotional burden it accumulated.

“Nobody uses that bridge, that’s why it’s abandoned,” says a man, pointing at it. Then he adds, in a grave tone: “It’s a bridge where several suicides have been recorded.”

This dark reputation is not unfounded. The year 2022 was one of the toughest in terms of suicides for Durango. 153 cases were recorded, a figure that raised alarm among authorities and civil society.

Many of these cases occurred on the Analco Bridge, particularly among young people between the ages of 20 and 35, an age group marked by pressure, uncertainty, and a lack of support networks.

This shocked Durango society, prompting a campaign to prevent more people from taking their own lives.

Thus, a citizen initiative was born, driven by educational institutions, mental health centers, religious organizations, and independent activists. They all agreed on one thing: this space needed to be addressed before it became a symbol of emotional abandonment.

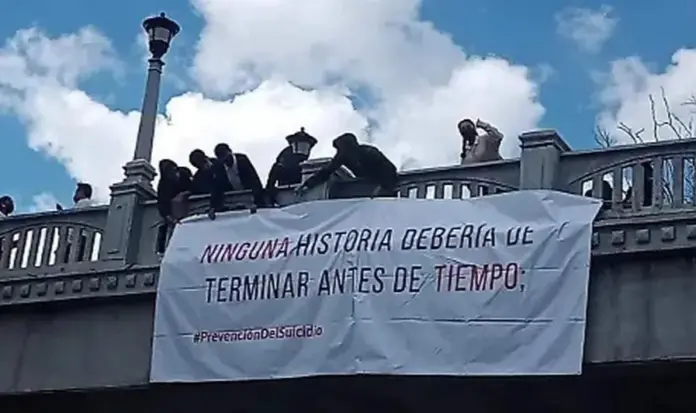

The bridge’s railings then began to fill with messages of encouragement: phrases written with markers, spray-painted, or hung on banners. One of the most memorable read: “Don’t do it, there are reasons to live.” Another, larger one, fluttered in the wind above the structure that was rebuilt in 2013: “No story should end before its time.”

Climbing the bridge at that time was like walking among frozen laments. Each step seemed to carry a portion of the collective pain, but also hope. Some climbed just to read those messages. Others simply walked around the site so as not to stir up past emotions.

Whether you believe or not in matters that go beyond a scientific explanation, the bridge holds an atmosphere that impacts the spirits of those who pass from the Analco neighborhood to the city’s main square.

Some say that a great feeling of sadness suddenly invades them, which dissipates the moment they cross this abandoned and completely vandalized structure, which leads to the belief that something “inexplicable” is there.

“It’s not just what happened there, it’s what you feel,” says Ana Luisa, a psychology student who participated in one of the first efforts at emotional intervention at the site.

“Some don’t believe in energies, but many agree that when you step onto the bridge, you experience a profound sadness, as if something were squeezing your chest. And when you cross it, it goes away.”

This atmosphere, which some consider esoteric and others symbolic, is not unfounded. The physical deterioration of the bridge—graffiti, trash, broken railings—is intertwined with the emotional deterioration it represents.

The promises of restoration, from both the municipal and state governments, have remained mere words. Since its reconstruction in 2013, nothing more than the bare minimum has been done to preserve it. The noble stone that was once the pride of the neighborhood is now covered in mold, neglect, and silence.

And yet, it remains a place of support. On May 10, 2024, while many people were celebrating Mother’s Day, a 22-year-old woman was emotionally supported by specialized personnel from the Yellow Line, a program operated by the State Public Security Secretariat.

The young woman was about to jump off the Analco Bridge, but was saved. Upon receiving treatment, she confessed that she was going through a crisis stemming from problems with her partner and the recent deaths of her mother and grandmother.

Meanwhile, the Analco Bridge remains, standing between institutional oblivion and the indelible memory of those who crossed it for the last time. A place that silently demands to be more than a tragic site. It demands to be heard, cared for, and healed.

Source: milenio