The debate over the death penalty in Mexico has been long and complex, and its constitutional regulation reflects the historical tensions between the severity of the punishment and respect for human dignity. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, both the legal framework and the social context permitted its application, only to move, step by step, toward its restriction and eventual abolition in the country.

The 1857 Constitution constituted the first systematic national attempt to limit the death penalty in Mexico. Article 23 stipulated that it would only exist while the national prison system was established, a difficult feat given the country’s economic ruin.

That being clarified, Article 23 states that the death penalty: “is abolished for political crimes, and may not be extended to cases other than those of traitors to the homeland in a foreign war, highway robbers, arsonists, parricides, murderers with malice aforethought, premeditated intent, or premeditated advantage, serious military crimes, and piracy as defined by law.” This provision reveals that the repeal of the death penalty was then seen as an ideal objective, contingent on the creation of a reliable prison system, and was limited to serious crimes.

Decades later, the 1917 Constitution established the conditions for this restriction. Article 22 established: “The death penalty is also prohibited for political crimes, and as for other crimes, it may only be imposed on traitors to the Fatherland in a foreign war, parricides, murderers with malice aforethought, premeditated intent, and advantage, arsonists, kidnappers, highway robbers, pirates, and those convicted of serious military crimes.”

The article, which maintains the same prohibitions on the death penalty as its predecessor, reiterates protection for those who commit political crimes and prohibits other punishments that modern society and law consider inhumane, such as mutilation, infamy, beatings, and torture.

As noted in the analysis by Olga Islas de González Mariscal, published by the Institute of Legal Research of the UNAM, the history of the death penalty in Mexico dates back to pre-Hispanic times, when it was applied using particularly harsh methods under Aztec law.

The Political Constitution of 1917

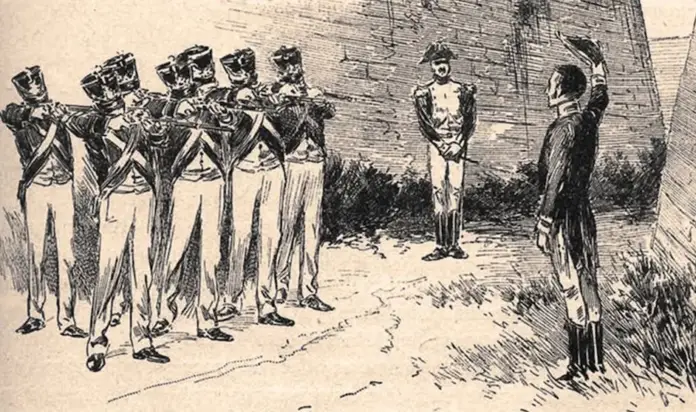

During the colonial period, executions coexisted with torture and other corporal punishments, and they continued to be used after independence. The first penal codes of the 19th century—such as that of Veracruz in 1835 and the federal code of 1871—regulated the death penalty in detail, although subsequent codes, both state and federal, progressively eliminated it from their catalog of sanctions.

The process of complete abolition was gradual; throughout the 20th century, state penal codes restricted the death penalty in their penal codes. The definitive elimination occurred in 2005, when a reform amended the Code of Military Justice to eliminate this punishment, and another to the Constitution itself with the same purpose, amending Articles 14 and 22.

Source: infobae